Review by Jessica Varin

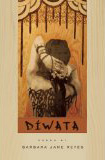

DIWATA

by Barbara Jane Reyes

BOA Editions, Ltd.

250 North Goodman Street, Suite 306

Rochester, NY 14607

ISBN 978-1934414378

2010, 88 pp., $16.00

www.boaeditions.org

Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to speak my mother’s first language.

Would I seem more Chinese and less white? Would I feel less fractionated? Would I blend into Asian-America with ease?

I don’t know the answers to these questions. I could spend a lifetime speculating; instead, I have chosen to create a new culture for people like me. There is no instruction manual, so I look to the creative work of those who stand at the intersect of two cultures.

Barbara Jane Reyes is busy (re-)creating a culture. In Diwata, she dreamweaves what is and isn’t remembered through prose and line broken poems. Her third collection explores metamorphosis amid two cultures and tongues.

In “Polyglot Incantation,” Reyes code-switches between Tagalog and English:

What twine or serpent skin binds

Silangan at kanluran

Pearl of the Orient

Este punto del embarco

Fractures archipelago

Ang mga anak mo ay nakakalat

Your children have scattered

Cielo el color de perlas negras

Do not forget that they have names

May sariling pangalan ang aming diwata

Diwata, the muse, is ever present. Reyes’ poems arrive wrapped in cedar and sinew. The natural world and the female body are inseparable. In “Again, She Tells The First Story,” the sea gives rise to Diwata:

Once, when there was no light, the wind danced with the sea, whose glassy surface became untamed funnels and silver-crested waves as she leapt and spun. The wind also spun and let out a mighty roar. You have heard this before, no? How earth convulsed as if laughing. How seafloor forced her fingertips upward. How she freed her body from the silent, murky depths.

Reyes is a storyteller. Her motifs are intricately woven and the arc is unmistakable. Half of me wants a loose end to grapple with; the other half is in awe of Reyes’ ability to carry such a cohesive, full-length collection.

In “Duyong 2,” she writes:

You are the girl whose new tail mimics a silver slicing razor.

Throughout the collection, Reyes uses sharpened knives as a metaphor for cultural dismemberment. Often, the cleaving is physical. In “Aswang,” the final poem, a woman’s body is separated into pieces:

I am the opposite of your blessed womb; I am your inverted mirror. / Guard your unborn children, burn me with your seed and salt, / Upend me, bend my body, cleave me beyond function. Blame me.

This is not the first measured taking. In “Call It Talisman (If You Must),” she recalls the way Filipina women bore the consequences of war. Once more, the female body is resigned to violence:

When the soldier came with his vulgar words, I leaned farther over the edge than I should have. But so venomous, his words. Upon the banks of the river for which my father was named, there, the soldier took me and took me, and the river could do nothing. I knew my brothers too could do nothing. There he tore me in two.

My child, your father’s eyes. My child, one day you will curse his name.

I expected a woman left choiceless, but I was simultaneously distraught by the powerlessness her male relatives endured. Reyes’ diverse and well-executed syntax also elevates the impact of this poem. The rest of the collection also benefits from her ability to turn language into itself.

Reyes’ attention to detail is sharp as the cinnamon and ginger she invokes. Where past yields to present, she carefully describes the metamorphosis:

Elders once brought her tobacco rolled and bound with hemp; now we bring bulk carton Marlboros. Once, spirits fresh in glass jars; now Spanish brandy, limes guava, and yams in baskets, salted fish in bundles. Now she is old but this firelight glows upon the face of a woman whose skin is sunned and taut; in her wide eyes we see sharp Lawin gaze, in her eyes we see sky.

“The Fire, Around Which We All Gather” is one of my favorite poems. Although the Philippines are cleaved by colonialism, the stories still hold.

This poetry collection provides a platform for the mythologies of a glorious and not-so-glorious past. In Diwata, creation happens time and time again.

Comments are closed.