Review by Alejandro Escudé

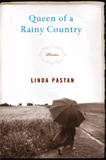

QUEEN OF A RAINY COUNTRY

By Linda Pastan

W.W. Norton & Company

500 Fifth Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10110

ISBN 0-393-06247-3

2006, 128 pp., $23.95

www.wwnorton.com

Is there one way to judge a book of poems? In the case of Linda Pastan’s new collection Queen of a Rain Country, I immediately knew she was going to be one of my favorite poets after reading only one poem in the collection. Pastan isn’t the type of poet you need to fiddle around with too long. Her work is accessible (in a good way), intriguing, and relevant. Her lines contain that wonderfully bittersweet immigrant essence, which I’m familiar with being the son of an immigrant family myself, and they also reveal a kind-hearted yet fiercely independent woman, as well as a loving, playfully cynical, passionate wife and mother.

And it’s the poems about matrimony which I like the best— deceptively simple poems such as “Marriage,” which begins, “He is always turning the radio on,/or the stereo, or the TV news,/and she is always shouting at him/through the noise to turn them off.” Forget that overwrought intellectualism which is so popular today in poetry; this is the real stuff. You wouldn’t know it from the quoted stanza, but this is a very positive poem about marriage, an interesting take on marital longevity and happiness. But the best poem in the collection on the subject is “I Married You”: “I married you/for all the wrong reasons,” Pastan writes, then concludes this short lyric with, “How wrong we both were/about each other, and how happy we have been.” This, in my opinion, is the essence of matrimony, and I enjoy the fact that it goes against the longstanding belief that you should be absolutely compatible with your mate if you are to be truly satisfied in a marriage. Pastan’s poem reveals a great truth: happy marriages are unions between people who often have clashing ideals, goals, beliefs, and personalities.

The other theme that Pastan deals with successfully is politics. Yes, that touchiest of themes that makes most poets, editors, and critics cringe. It’s very difficult to write a good political poem, but Pastan does it right simply because she gives it to you straight. In “September 11, 2001,” Pastan writes, “I have been listening to disaster/on the radio all day long/and sometimes on television./Outside the trees are unbelievably/green, autumn has hardly begun/its devastations.” This is not only true to the common American experience on that horrible day, but it’s also prophetic. Pastan seems to predict the coming war and foretells the endless downward spiral the tragic event sparked. In a poem about the Abu Ghraib scandal, she writes, “What we are capable of/is always astonishing,/though never quite a surprise.” These are not poetically grand lines, I know. But aren’t they what you want to hear right now at this particular juncture in history? Pastan says what we’ve all been saying, or thinking, and it’s not a bad thing, it’s a wonderful thing–it’s what I believe good poets do.

One of the things I love to find in a poet is permission, the permission to write about what everyone says is too difficult or trite. Besides politics, one of the hardest themes to write about is poetry itself, yet Pastan offers several poems on that subject as well. In “For the Sake of the Poem,” she writes, “I am an addict who needs/her daily fix of language.” As a poet, these lines speak directly to me. I relate to this obsessive need to tinker with words. She goes on to write: “For the sake of the poem/old age is put on hold./What wouldn’t I do for the sake of the poem?” Such lines do not contain the denseness of Yeats, the stream of consciousness quality of Ashbery, or the metaphorical muscle of Plath, but they speak the truth, a truth that is wonderfully clear, robust, and resonant. Pastan is a poet’s poet, but she is also a poet for the masses. And this is exactly the kind of poet I feel like reading in today’s confusing and often terrifying times.

Comments are closed.